And it's much, much worse

Back in 1970, Alvin Toffler predicted the future. It was a disturbing forecast, and everybody paid attention.

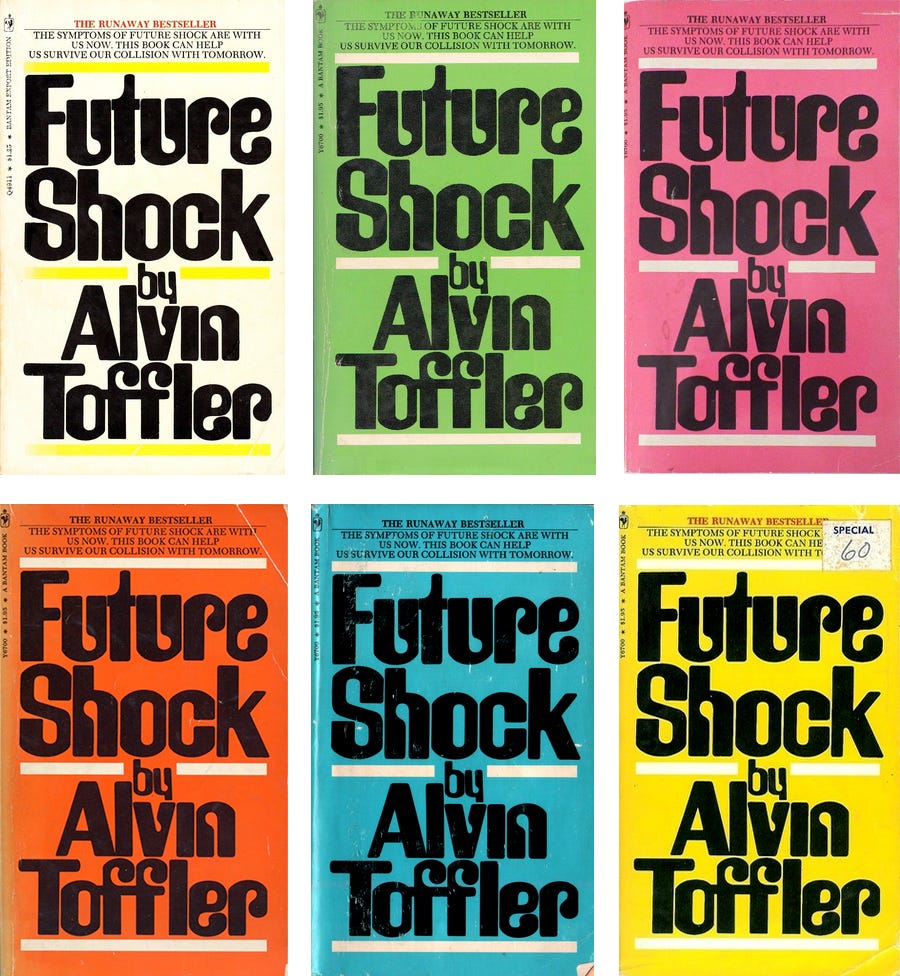

People saw his book Future Shock everywhere. I was just a freshman in high school, but even I bought a copy (the purple version). And clearly I wasn’t alone—Clark Drugstore in my hometown had them piled high in the front of the store.