“The redundancy in the above recommendations does not help.”

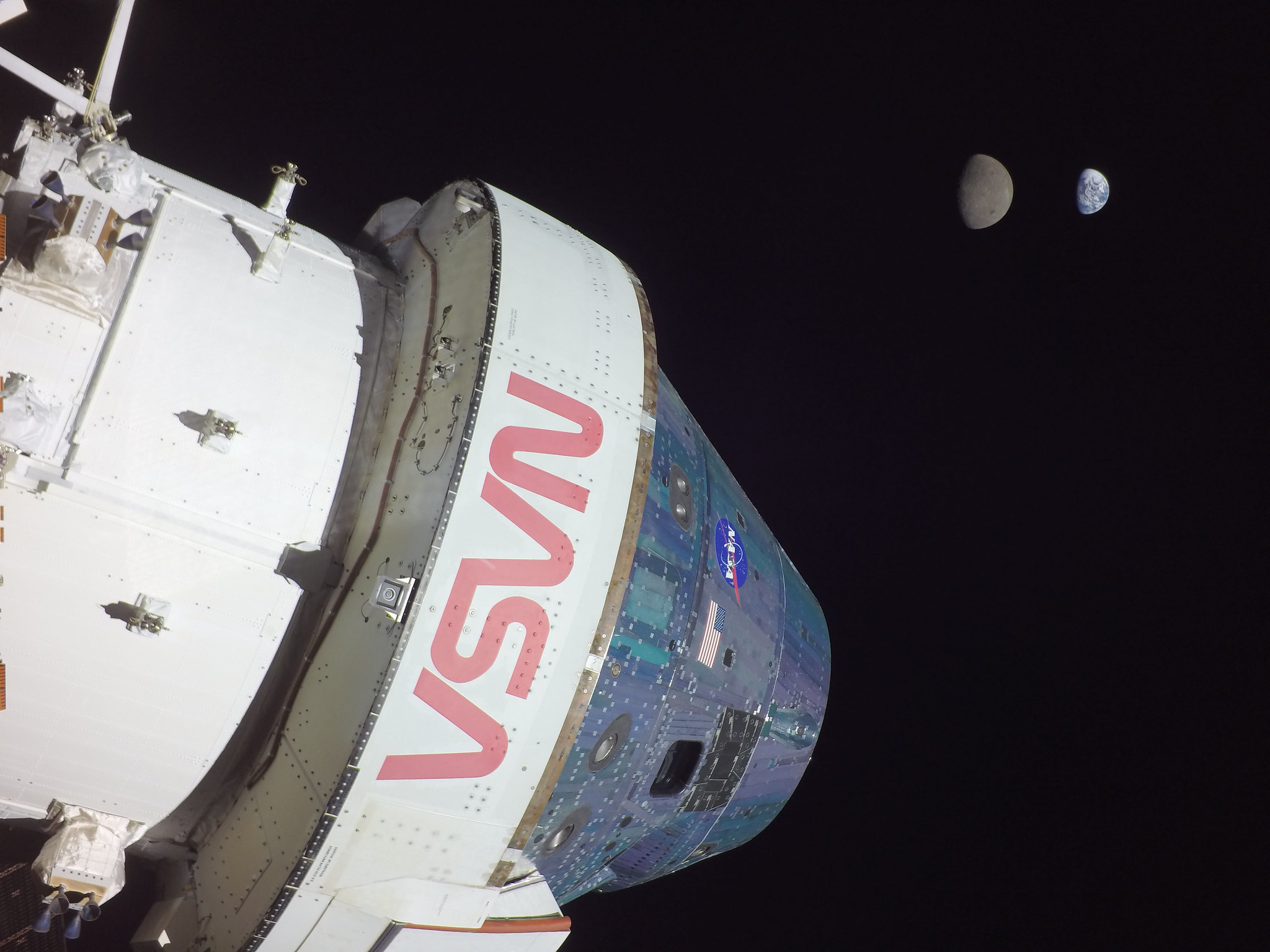

Orion, the Moon, and Earth in one photo in December 2022. Credit: NASA

NASA’s acting inspector general, George A. Scott, released a report Wednesday that provided an assessment of NASA’s readiness to launch the Artemis II mission next year. This is an important flight for the space agency because, while the crew of four will not land on the Moon, it will be the first time humans have flown into deep space in more than half a century.

The report did not contain any huge surprises. In recent months the biggest hurdle for the Artemis II mission has been the performance of the heat shield that protects the Orion spacecraft during its fiery reentry at more than 25,000 mph from the Moon.

Although NASA downplayed the heat shield issue in the immediate aftermath of the uncrewed Artemis I flight in late 2022, it is clear that the unexpected damage and charring during that uncrewed mission is a significant concern. As recently as last week, Amit Kshatriya, who oversees development for the Artemis missions in NASA’s exploration division, said the agency is still looking for the root cause of the problem.

This week’s report from the inspector general—an independent office charged with investigating crime, fraud, waste, and mismanagement involving NASA programs—provides some additional details but does not change the overall conclusion. The unresolved issues with the heat shield pose a significant risk to NASA’s plans to launch Artemis II in September 2025. Probably the most notable new information came in the form of two images that showed previously undisclosed details about the deep divots in the Orion heat shield after Artemis I.

A bit peeved

However, what was striking about this report is NASA’s response. Buried at the end, on page 36, there is a distinct tone of petulance in the remarks from Catherine Koerner, the associate administrator for Exploration Systems Development Mission Directorate. Her role at NASA, in effect, is to oversee development of Orion and other hardware used for missions into deep space.

After concurring with each of the six recommendations in the inspector general’s report, Koerner made the following comment:

“NASA is dedicated to continuous enhancement of our processes and procedures to ensure safety and address potential risks and deficiencies,” she wrote. “However, the redundancy in the above recommendations does not help to ensure whether NASA’s programs are organized, managed, and implemented economically, effectively, and efficiently.”

A careful reading of the second sentence reveals that Koerner feels that the inspector general’s efforts are both redundant and unhelpful. This is not accidental language. Koerner’s response was certainly reviewed by NASA’s senior managers, who could have flagged and removed the text. And yet they went through with it.

After publication of this story, and in response to a query made on Wednesday evening, NASA issued the following statement about Koerner’s remarks:

“That is not a correct interpretation of the agency’s response. As stated, NASA recognizes the critical role of the Office of Inspector General, and furthermore, the agency values the Office of the Inspector General’s attention to the Artemis campaign. NASA’s response highlights that analysis and mitigation of the issues identified during Artemis I have been underway since the conclusion of the mission. NASA engineering teams contributed fully and openly to the Office of the Inspector General’s report by providing data directly resulting from that work and appreciate the report’s summary of those pre-existing efforts in the Recommendations section. NASA remains committed to ensuring the safety of the Artemis II flight next year, and to future missions.”

So what’s going on here?

NASA officials are clearly feeling the pressure when it comes to Artemis. The second mission, a flyby around the Moon, is supposed to be the relatively easy one. The really difficult mission, a lunar landing involving Orion docking with SpaceX’s Starship in lunar orbit, is much more ambitious. Politically, there is a lot of pressure to deliver on both, and Congress is watching closely as NASA faces probable delays.

This week, during a hearing of the House Science, Space, & Technology Committee to consider NASA’s budget for fiscal year 2025, the very first question from Chairman Frank Lucas concerned possible changes to Artemis III. Referring to an article in Ars Technica about NASA’s internal deliberations about modifying the mission profile to have Orion and Starship dock in low-Earth orbit, Lucas asked the NASA administrator what was happening.

“This is part of our commercial program, and SpaceX signed up to land in September of ’26,” Nelson replied, referring to NASA’s plan to land its astronauts inside Starship in September 2026. “Now that is what is provided in the contract. The article that you’re referring to is speculation. Well, what happens if they’re not ready? Well, naturally people think about these things. But the plan is to land, and it would be two astronauts of the crew of four that would get into the lander and go down and land.”

The inspector general’s report included new images of Orion’s heat shield.

Credit: NASA Inspector General

The inspector general’s report included new images of Orion’s heat shield. Credit: NASA Inspector General

But even Nelson acknowledged that NASA was asking a lot of its contractors for Artemis III. Later, he added, “And I might say, think about the Apollo program and the Artemis program. Artemis III, the first lander that SpaceX is contracted for, is the equivalent of Apollo 9, Apollo 10, and Apollo 11. So it’s a very accelerated program.”

Amid this backdrop of political pressure, NASA officials feel the usual frustrations with the myriad review boards that dig into its programs and look for problems. In addition to its own inspector general’s office, there is the Government Accountability Office, the Aerospace Safety Advisory Panel, the NASA Advisory Council, the International Space Station Advisory Committee, and more. NASA officials must regularly meet with and respond to questions and concerns from these organizations.

Transparency, please

Koerner’s remark about redundancy almost certainly reflects the space agency’s peevishness with the continual oversight of these bodies. In effect, she is saying, we are already aware of all these issues raised by the inspector general’s report. Let us go and work on them.

However, the reality is that for those of us outside of the government, the inspector general provides valuable insight into supposedly public programs that are nonetheless largely shrouded from view. For example, it is only thanks to the inspector general’s office that the public finally got a full accounting for the cost of a single Space Launch System and Orion launch—$4.2 billion. NASA, for years, obscured this cost because it is embarrassingly high in an age of increasingly reusable spaceflight.

It is somewhat chilling to see government officials openly attack their independent investigators. These officials are appointed by the president and confirmed by the US Senate. When President Trump did not like the findings of some of these officials in 2020, he purged five inspectors general from the Department of Health and Human Services and other agencies in six weeks. The Economist characterized this as a “war” on watchdogs.

It may be frustrating for NASA officials to have to repeatedly tell the public how it is spending the public’s money. But we have a right to know, and these kinds of reports are essential to that process. My space reporter colleagues and I often have the same questions and want these kinds of details. But NASA can tell us to pound sand, such as the agency did with coverage of the Artemis I countdown rehearsal in 2022.

Listing image: NASA

Eric Berger is the senior space editor at Ars Technica, covering everything from astronomy to private space to NASA policy, and author of two books: Liftoff, about the rise of SpaceX; and Reentry, on the development of the Falcon 9 rocket and Dragon. A certified meteorologist, Eric lives in Houston.